Driving is hard, but humans make it look easy. We're UT Dallas's applied autonomous driving project, and we're making driving look easier than ever.

YouTube

LinkedIn

LinkedIn

project.nova@utdallas.edu

Latest posts

New Members and Goals! 23-24 11/15/23Planning with cost maps 2/13/23

What's up with Nova? 2/2/23

New members (and goodbyes) 10/23/22

Why we like Nova (video) 8/27/22

All posts ⟶

Reorganizing Our Stack

by Will Heitman

We reached our first milestone about a month ago, and it felt like we had finished a marathon. What now? It was time to tackle the menace of any major project: technical debt. In our software, this means removing any hacks that we threw together and all the other shortcuts that we took through Demo 1. The best place to start is at the foundation: the organization of the code itself.

About containers

For most of computing history, our operating systems were responsible for mediating between the unruly applications running on our machines. But the OS doesn’t always work perfectly: Resource-hungry applications can hog our machine’s memory, causing the whole computer to “freeze”. Bad code in a single program can cause the entire OS to “blue screen”. These imperfections are annoying on, say, laptops, but they’re much more serious on autonomous cars zipping down the street.

We can fix this with a somewhat new approach to software architecture called “containerization”. The idea is simple: Put each program into its own container. Each container mimicks an entire OS, so each program thinks it has the whole machine to itself. Since each container is (to really simplify things) a virtual machine, we can fine tune each container to play nicely with the other containers in our stack.

Those resource-hungry programs from earlier? We can cap the resources of the container so those memory hogs don’t interfere with the other programs’ performance. Those unstable programs that caused “blue screens” earlier? Although we should always strive to prevent crashes in the first place, the worst-case scenario is now crashing a single container, not the whole machine.

There are lots of other benefits to containerization: Security, portability, clarity, and so on. Accordingly, this approach to software design has really taken off.

So how do we take this concept of containers and apply it to our code?

Our approach: The orchestra

We use Docker, a highly popular container framework, to wrap each of our ROS nodes up. Specifically, we create a “frame” image that has all of our tools (Autoware.Auto, ROS2, custom libraries, and so on) pre-installed. For each ROS node, we simply copy the code into our “frame” image, build the ROS node inside the image, and generate a Docker container. Just like that, we’ve nestled a ROS node nicely into a virtual environment.

Now that all the pieces of our stack are inside their own containers, we use a tool called Docker Compose to run all of our containers in tandem. This is not as simple as executing docker run [image] on all of the pieces. We write a special file called docker-compose.yaml that describes exactly how each piece should be run: What network privileges each container has, what parts it depends on, how much memory it can receive, and so on.

So now we have a single file that runs all of our containers, and each container has its own piece of our stack. We can now run our entire stack with a single command: docker-compose up. Done.

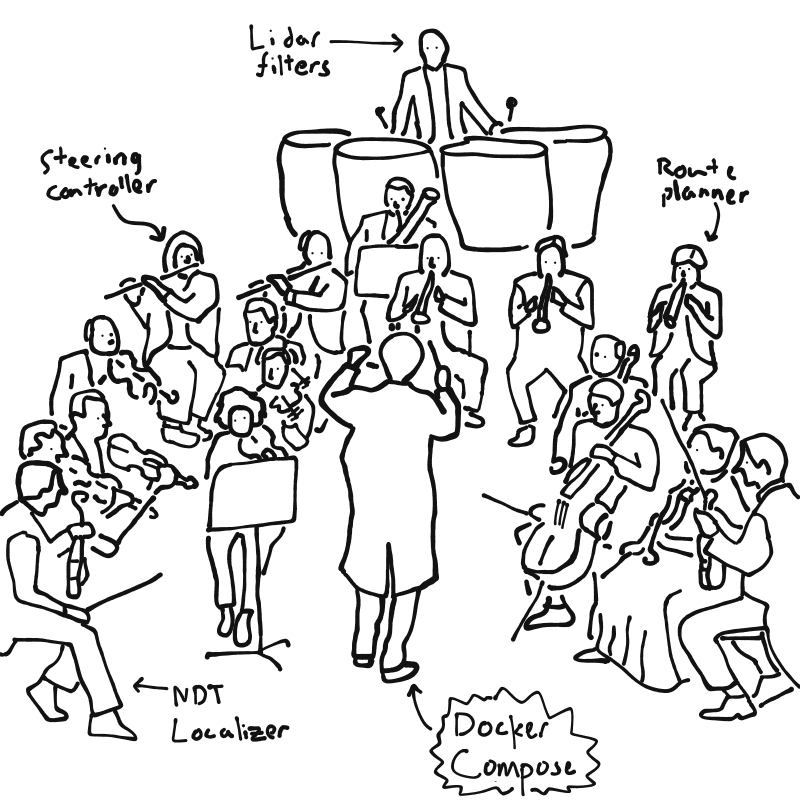

We can think of Compose as the conductor of an orchestra. Each container is a musician, and with the help of the conductor, the musicians create beautiful harmony. When a musician plays too fast, or hits the wrong note, the conductor notices and takes action.

This “orchestra” approach is a much safer approach than our previous software approach, where all the musicians just play their own tunes, creating nothing more than noise. Instead of a well-tuned symphony, our software stack resembles kindergarteners with kazoos. When I get behind the wheel of a self-driving car, I’d gladly take the symphony over the kazoos.

Custom images

I mentioned earlier that each node is put inside a “frame” image that builds the ROS node and runs it. Here are some more details on exactly how our images are structured.

In Docker, images are created using Dockerfiles. These files are instructions for how a container is built. Remember that a container is (basically) a virtual machine, so Dockerfiles do things like install software, create users, and anything else necessary to set up an environment for our code.

Dockerfiles start with a FROM instruction that inherits a parent image. In our base container, we start by inheriting the official ROS Foxy image, which in turn inherits the offical Ubuntu image. In a single line, our custom base image now has Ubuntu and ROS installed. The rest of the Dockerfile downloads and builds Autoware, along with its many dependencies.

Our pillar image inherits from base, then adds any custom libraries that we write, all of which are stored in a roslibs folder in our repo root. At the moment, this is just two custom libraries. We separate this process from base because we don’t want to rebuild Autoware every time we add or modify a custom library.

Finally, our frame image inherits pillar, then copies the code from a ROS package or workspace (specified in our Docker Compose config) and builds it using colcon. When the image is run, it launches our nodes using a ROS launch file.

All of our custom images are stored in, you guessed it, the images directory.

Using VDE

Our entire stack, including the Docker configs, ROS param files, map data, and of course our program source code, is wrapped in a bundle that we call the Voltron Development Environment, or VDE (this is a nod to ADE)

Once our stack has been writte, the only thing left is to run it. As mentioned, this is done using docker-compose up.

Behind the scenes, Docker creates a virtual network interface for each container, then connects the containers to a shared network. This means that although the files and computing resources are virtually isolated in each container, the network is shared among them. This allows ROS to communicate seamlessly across the whole stack, and it also lets us communicate with the stack in the host OS, outside of Docker.

Future work

VDE is still a baby, and it has a lot of growing to do. We plan on adding network rules to make our virtual network more secure. We’d like to add restart policies to each container, which allows us to handle unexpected program errors safely. Of course we’ll add more ROS packages as our project grows. Conspicuously missing from our stack is a user interface, so we’d like to add a web server that serves a web UI.

Conclusion

You can view and download our code from our GitHub repo, so go check it out! If you have any suggestions or questions about our work, feel free to reach out to us.